Rejuvenation in rural Ireland in response to the COVID-19 induced urban-to-rural migration phenomenon

Rejuvenation in rural Ireland

- admin

- 0 comments

- 627 views

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to discuss the paradigm shift in residential choices induced by the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. Firstly, the resilience of the rural regions belonging to the Northern Periphery and Arctic Program will be explored—the challenges brought about by COVID-19 within their tourism sectors, and the opportunities for rural revival generated by the current shifts in workplace mobility. The paper will then delve deeper into the case study of Ireland. The pre-existing issue of Ireland’s one-off housing and suburban sprawl will be explored, and the extent to which the regional plan “Our Rural Future” will tackle these issues by optimizing building density and dwelling typology in the post-COVID-19 era.

© 2021 The Authors. Published by IEREK press. This is an open access article under the CC BY license

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Peer-review under responsibility of ESSD’s International Scientific Committee of Reviewers.

Keywords: Northern Periphery and Arctic Program, rural rejuvenation, “one-off” housing, second homes, regional planning, development, remote working, building density, dwelling typology, COVID-19

1 Introduction

We live in an era of intense urbanization. Global trends indicate that populations are projected to increasingly concentrate in urban regions— leaving small towns and rural areas to face youth out-migration, brain drain, and increasingly ageing populations (Fisher, 2021). These trends are also evident in the case of the 9 partners of the Northern Periphery and Arctic Program (2014-2020), a transnational cooperation between Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Ireland, Northern Ireland, the UK, Faroe Islands, and Greenland (NPA, 2021). The Northern Periphery Program aims to help these remote communities based in the northern fringes of Europe to harness their potential for innovation, entrepreneurship, and growth (NPA, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact in disrupting old patterns and attitudes, from employment practices to perceptions regarding urban versus rural living (Nordic Talks, 2021). Several factors defining the periphery such as a low population density, localized services, and higher levels of civic engagement have added to the resilient nature of the periphery during the pandemic. COVID-19 has impacted not only the daily lives in rural communities of these NPA regions, but also their local tourism (Fisher, 2021a). The pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have demonstrated the economic and social consequences of an excessive dependency on international tourism during crises—with threats of further spreading pandemics, and significant drops in trade and income (Fisher, 2021a). Advocates of sustainable tourism believe that the lessons from COVID-19 will reinforce the need to balance sustainable community development with the well-being of inhabitants (Benjamin et al, 2020). This form of “regenerative tourism” may promote trends of tourism equity and a revival of the rural areas in the post-pandemic age.

The current pandemic-induced shift in workplace mobility could help achieve such a rural revival. As lockdowns and social distancing restrictions force the greater part of the global population to stay home for extended periods, access to green spaces and large private spaces have become a luxury for many (Åberg et al., 2021). Competing trends of a second-home boom, advancements in ICT and teleworking, and a prevailing counter-urbanism sentiment have the potential of spurring rural rejuvenation by attracting city dwellers to relocate, at least seasonally, to sparsely populated rural areas (Åberg et al., 2021).

Understanding the broader context and characteristics of the NPA regions in Europe provides further insights into the case study of Ireland. Similar to the other regions part of the Northern Periphery and Arctic Program, rural Ireland has also been confronted by several pressures with the advent of the Coronavirus pandemic. A large elderly demographic and difficult access to healthcare facilities have critically hindered the ability of some of Ireland’s largely dispersed rural regions to counter the pandemic as effectively as their urban counterparts (OECD, 2020). A large contributor to this issue is the pre-existing tradition of Ireland’s suburbanized settlement patterns with its “one-off” housing estates. These are detached, private properties in the countryside; c.a. 26% of the two million occupied housing in Ireland can be categorized as “one-off” housing estates (Central Statistics Office, 2021). These dwellings are representative of a deeper issue linked to Ireland’s conservative socio-political culture and fondness for the rural idyll (McDonald & Nix, 2005). Rural communities are worried about the constant threat to rural institutions and the lack of critical infrastructure essential towards maintaining the cohesiveness of communities (IFA, 2015)

Presently, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the suburbanization process. This is due to a shift from on-site to remote working in cities, which has softened the demand for commercial office spaces (Noonan, 2021). Several Irish towns and villages have thus transformed into low-density, temporary, green havens for the urban generated rural dwellers. This has consequently led to an increase in demand for affordable individual housing units in the outskirts of counties Galway, West Cork, Mayo, Westport, Roscommon, Kerry, and Donegal (Hutton, 2020). Amongst homebuyers, the focus has shifted from the traditional commuter belts, and to the rural, west coast (Meehan, 2021). Northwest Ireland generally has the highest proportion of one-off housing; the region is also one of the most economically disadvantaged of the country with few urban settlements (Central Statistics Office, 2021).

Reflecting upon the shift in attitudes of potential home buyers, the Irish government decided to execute its regional development plan “Our Rural Future: 2021-2025”, to tackle the dispersed suburban settlement issue (Dept., 2021). The plan aims to reverse acute rural decline and address rural housing in a broader regional development and settlement context (Dept., 2021). In addition to dealing with the historical pattern of dispersed development, the plan seeks to protect regions under strong urban influence from unsustainable over-development. This will be achieved with the introduction of sustainable, carbon-neutral, and well-integrated walkable communities that are in proximity to amenities and collective services (Dept., 2021). Alongside socioeconomic rejuvenation, the country’s cultural identity will be enriched by the urban-to-rural migration since Ireland’s heritage lies in the heart of its rural landscape, flora, and fauna (Corcoran, 2018).

The aim of this paper is to discuss the paradigm shift in residential choices and explore the policy approach to rural development in light of the needs and opportunities highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Firstly, the phenomenon of peripherality and the impacts of the pandemic will be investigated in the larger context of the NPA regions. Aspects such as the resilience of the peripherality and impacts of the pandemic on local tourism in the NPA regions will be further evaluated. Next, the paradigm shift regarding workplace mobility and the favor for varied typologies of second homes—cabins, cottages, seasonal holiday accommodation, and one-off housing—will be discussed in order to tackle territorial inequalities and evaluate opportunities for rural revival. The paper will then further delve deeper into the case study of Ireland—first discussing the dominant issue of Ireland’s suburban sprawl and the prevalence of “one-off” housing. Then the paradigm shift from urban to rural regions during COVID will be explored alongside the contributing socioeconomic factors. Finally, the government’s regional development policy, “Our Rural Future: Rural development policy, 2021-2025” will be evaluated, which offers solutions to these issues.

2 COVID-19 impacts and recovery in the Northern Periphery and Arctic Program

The Northern Periphery and Arctic Program (2014-2020) is a transnational cooperation between 9 partners: Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Ireland, Northern Ireland, the UK, Faroe Islands, and Greenland (NPA, 2021). Despite variations in geographical features, these regional partners share a number of opportunities and joint challenges such as low population density, low economic diversity, peripherality, abundant natural resources, and high susceptibility to climate change (Fisher, 2021). A sparse population growth, youth out-migration, brain drain, and an increasingly ageing population are their defining demographic characteristics (Fisher, 2021). The Northern Periphery Program aims to help these remote communities harness their potential for innovation, entrepreneurship, and growth in a resource-efficient way, thus paving the way toward self-sufficient, circular economies (NPA, 2021).

As Covid-19 spread throughout Europe in spring 2020, the NPA Monitoring Committee initiated the “NPA Covid-19 Response Call,” supporting seven projects that aimed towards understanding the impact of Covid-19 across the NPA regions with regard to (A) Clinical aspects, (B) Health and wellbeing, (C) Technological solutions, (D) Citizen engagement/community responses, (E) Economic impacts and (F) Emerging themes, focusing on care homes and university campuses (NPA, 2021). Investigating the impacts of the pandemic on NPA’s peripheral regions reinforces the need for a fresh perspective regarding peripherality and localism, as well as a proper assessment of assets, strengths, and opportunities that these remote regions offer during times of crisis.

2.1 Resilience of peripherality in the NPA regions during COVID-19

During the pandemic, a common trend across all NPA regions was that rural communities—due to their size, small-scale networks, and interdependent nature with inbuilt cooperative systems—had a more dramatic response to the pandemic through community-based initiatives (Nordic Talks, 2021). Rural regions with their smaller populations and close-knit communities were able to provide greater civic engagement through volunteering, voting, and immunization (Fisher, 2021b). In the context of the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland, the general population was permitted to book COVID-19 tests utilizing a contact tracing app. Developed in just 10 days by volunteers, the app functions without the intervention of a doctor—thus streamlining the testing process, quickly shutting down community transmission, and reducing the workloads of doctors (Fischer, 2021b). In the case of islands Uist and Barra in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, the COVID-19 outbreaks were effectively suppressed by bottom-up initiatives of island communities, often going a step further than public mandated measures (Nordic Talks, 2021). A survey by Scottish Rural Action suggests how well-resourced local organizations and stakeholders such as Community Councils, Development Trusts, local businesses, and statutory sector organizations were able to respond to local needs in targeted, dynamic ways (Scottish Rural Action, 2020). Such micro-and small enterprise sectors often act as breeding grounds for new business developments and innovations within a wide range of economic sectors, ranging from the bioeconomy in the Nordic regions to the healthcare technology of Northern Ireland (Fisher, 2021b). Micro-businesses in the primary sector are crucial in the delivery of critical services, from food through servicing machinery to retail, which cannot be easily imported from outside to the local economy (Fisher, 2021b). These are aspects that contribute to the resilient nature of the peripheral economy, which is often characterized by a loyal local customer base.

The resilience of the periphery is evidenced by the relatively low mortality rates, hospitalization numbers, and infection rates per capita—a staggering twofold difference between urban and rural centers (Nordic Talks, 2021). Finland saw that its peripheral districts, in contrast to its capital city Helsinki, have been able to keep the infection rates comparatively low (Fisher, 2021). This phenomenon can be attributed to the low accessibility, low population density, and increased dispersion of the remote areas. These aspects are inhibitory factors, generally perceived as negative in the context of modern-day globalization—yet in the light of the pandemic, they have aided in quick organization and reaction (Nordic Talks, 2021). The Highlands and Islands of Scotland suffered from less severe impacts of COVID-19 due to high levels of vaccination (Fisher, 2021b). By February 2021, the Outer Hebrides had the highest proportion of its population vaccinated of Scotland’s health board, Orkney the second-highest, and Shetland the fourth-highest (Fisher, 2021b). In the case of Ireland, the pandemic has brought a new appreciation of community health care with successful campaigns such as “No Doctor No Village,” especially general practices in remote peripheral locations that enjoy high patient trust (Nordic Talks, 2021). This has been transformative within Irish health services seeking to strengthen relationships and lines of communication and integration” (Nordic Talks, 2021). Investing in localized services and preventative health care is economically beneficial if delivered locally so that patients do not incur the travel going to centralized services in cities.

However, there have also been outliers—several individual communities and peripheral regions have been hit harder by the second and third waves of COVID-19 than the first. For example, the regional comparisons in Sweden demonstrate a mixed picture (Svanberg, 2021). In July 2020, Northern Sweden demonstrated the highest COVID-19 cumulative death rate—23.6 per 100,000—in the Arctic region (Svanberg, 2021). A shift in workplace mobility and opportunities for remote working contributed to lower rates in the Arctic region from mid-March through June—with the exception of Northern Sweden, which exhibited a sharp rise of infections due to its relaxed cross-border policies (Petrov et al., 2020). A number of island communities in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Ireland have been hit significantly higher by COVID-19 compared to Finland and Norway—which can be linked to eased travel restrictions, general seasonality of the coronavirus, and vaccination numbers (Fisher, 2021b). Implementation of targeted measures in the Arctic region, based on the vulnerability of locations, businesses, and population composition, are potential means that could have helped avoid hard-hit regions (Petrov et al., 2020).

2.2 Impacts of Covid-19 on tourism across NPA Regions

Prior to the pandemic, the development of mass tourism had been one of the major economic drivers adopted by the national governments and peripheral communities in the NPA regions to help provide jobs, diversify economies and address demographic challenges (Fisher, 2021a). Tourism had been noted as one of the fastest-growing economic sectors across NPA regions such as the Nordic countries, Scotland, and Ireland (World Tourism Organization, 2020). The Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland are examples of fishing-based economies that have recently transitioned into tourism-based economies (Fisher, 2021a).

Mass tourism however involves key challenges—an imbalanced seasonal distribution of visitors across the year, short-term employment opportunities, coupled with an increasing trend of outmigration to urban areas leading to an ageing labor force (Nordic Talks, 2021). During the summer tourist season, some small Irish islands receive thousands of day visitors every day, which puts huge pressure on public and community infrastructure, community life, and priorities (Nordic Talks, 2021). This results in often limited, poorly distributed, low-skilled employment opportunities in remote regions. Adding to the detrimental nature of mass tourism, Covid-19 and subsequent lockdowns have demonstrated the economic and social consequences of an excessive dependency on international tourism during crises—with threats of further spreading pandemics, and significant drops in trade, income, and employment (Fisher, 2021a). The shrinking demand for tourism during the pandemic occurred almost overnight amongst overseas overnight tourists, cruise boat passengers, festivals and event attendees, and business visitors. The aviation sector belonging to the Highlands and Islands region of Scotland was seriously affected, with passenger numbers falling by 78% between April and November 2020 (Fisher, 2021a). In the context of the Nordic countries, the WTO indicates that the region had been affected by an estimated 75% decrease in international tourism between April and June 2020 (Fisher, 2021a).

Overall, COVID-19 has demonstrated that local and regional economic growth depending solely upon tourism is no longer a viable strategy when confronted by crises such as pandemics and the climate crisis. Advocates of sustainable tourism believe that the lessons from COVID-19 will reinforce the need to balance sustainable community development with the well-being of inhabitants (Benjamin et al, 2020). This form of “regenerative tourism” will promote tourism equity and a revival of the rural areas in the post-pandemic age (Benjamin et al., 2020). There is significant evidence of businesses that have adopted and survived this sudden downturn in international tourism. For example, 52% of the BCCDC survey participants belonging to the tourism sector in Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands believe that COVID-19 has prompted business models and tourism development strategies to accommodate local tourism, remote or distant tourism, staycations, and second homes (Fisher, 2021a). For many communities and businesses, this focus on domestic markets has brought tourist businesses closer to all-year-round trade and income (Nordic Talks, 2021).

2.3 Paradigm shift in workplace mobility across NPA regions

An excessive dependency on international tourism has been one of the driving factors diminishing economic resilience in peripheral communities during the pandemic. NPA regions now have the opportunity to encourage rural revival amidst another emerging theme—a paradigm shift in workplace mobility and a renewed interest in rural living among urban dwellers (Åberg et al., 2021).

COVID-19 has significantly disrupted old patterns and attitudes, from employment practices to perceptions regarding rural living. Over the course of the pandemic, peripheries have become a refuge for maintaining health, strengthening community ties and local economies (Nordregio, 2021). As lockdowns and social distancing restrictions force a greater part of the global population to stay home for extended periods, access to green spaces and large private spaces have become a luxury for many (Åberg et al., 2021). In several instances, these “digital nomads” and “knowledge workers” are escaping to the rural regions to access assets like affordability, space, and access to nature (Nordregio, 2021). However not all rural communities will be able to capitalize on this rural renaissance without a sufficient supply of services, communal amenities, and infrastructure (Åberg et al., 2021). As people increasingly divide their time between their urban permanent home and their rural second home—this trend may further suggest the need for improvement within the connections between the urban and rural areas (Åberg et al., 2021). The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 states, “the recent COVID-19 pandemic makes the need to protect and restore nature all the more urgent, the pandemic is raising awareness of the links between our own health and the health of ecosystems,” – urging for investment and policy development promoting the revitalization of rural areas (European Commission, 2021). Effective implementation of infrastructure and use of distance-spanning technologies could also help contribute to a change of employees’ preferences regarding residence, which would, in turn, revitalize the counter-urbanization processes and counteract the brain drain from peripheral areas to urban centers (ESPON, 2019). The ability to offer suitable housing options like zero-energy and shared housing solutions is also vital to these communities to remain attractive to the highly educated, and at the same time maintain a source of revenue for local craftsmen and businesses (Nordregio, 2021).

Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland have noted a rise in people relocating to their seasonal residences or second homes during lockdowns and stay-at-home orders (Fisher, 2021). Second homes are not a new trend in Nordic cities; historically, the region has had a strong tradition for second homes (Slätmo et al., 2019). As a result of the ongoing urbanization patterns and the increasing compactness of the Nordic cities, many choose to acquire a second home in the outskirts of the cities- equipped with private gardens and access to nature (Slätmo et al., 2019). Half of the population in the Nordic region has access to a second home or “cabin” that is utilized during summer or winter seasons or during weekends. There is thus a prevalence of a counter-urbanism sentiment amongst the second-home owners and seasonal tourists, also known as the “voluntary temporary populations” (Slätmo et al., 2019). The changing dynamics of the Nordic labor markets, provided by the shift to remote working and off-site learning, are strengthening the culture of second-home ownership and cabins (Nordregio, 2021). Inari, Finland’s largest municipality, is an example of this. Demographic analysis shows that the majority of people buying second homes in Inari are wealthy migrants from the capital Helsinki and other large cities. Remote working possibilities for workers within the fields of IT or teleworking (one million Fins are now engaged in the field of teleworking) permit them to work off-site and reduce commute (Nordic Talks, 2021). In another case, Swedish media (DN) reports an emerging post-COVID trend of young Swedish families moving from Stockholm to other peripheral regions in search of more spacious facilities where work and family life can both be combined, after over 40% of working professionals were sent into work-from-home mode (Fisher, 2021a). This counter-urbanism sentiment is strengthened also after persistently booming housing prices in urban areas and expensive flats with smaller living areas in dense urban settings (Fisher, 2021a). Similarly, North Iceland enjoyed an active tourist season in 2020 based entirely around domestic tourism—reporting an increased interest in staycations, as well as their own regional history, nature, and traditions. There have been reports of people normally based in Norway and Denmark who have moved to the Faroe Islands since they can work remotely with fewer Covid-19 restrictions (Fisher, 2021a).

The islands and idylls of rural Scotland are attracting the lockdown-weary (Cundy, 2020). After Scotland’s first lockdown froze the market for three months, parts of the country experienced interest in suburban and rural properties (Cundy, 2020). The massive growth in popularity of the Isle of Skye in Scotland is an example of this (Fisher, 2021a). 40-50% of the local housing stock in the Isle accounts for holiday accommodation, cottages, and seasonal homes (Cundy, 2020). The area is hugely popular with incomers, often retirees, buying second homes and retiring to the island. They are not part of a cultural heritage that has been passed down generations in islands like Skye, and price local families, who might continue this cultural heritage, out of the housing market (Cundy, 2020). This post-lockdown paradigm shift exacerbates the already unsustainable situation in many islands which are struggling to sustain tiny communities in the face of youth depopulation as well as the survival of Gaelic languages in the heart of island communities (Fisher, 2021a). In this way, the apparent welcome trend of skilled professionals moving into peripheral regions can undermine the sustainability of the peripheral communities that they find so attractive (Scottish Rural Action, 2020). The retirees migrating to peripheral areas may not be able to contribute much longer to economic activity and may well require significant health care in the future (Cundy, 2020). This negative demographic development in remote and peripheral areas is partly rooted in unfavorable house market conditions over the last few decades, including higher costs to build social housing in peripheral areas, the poor quality and often low value of housing, and significant land issues for securing housing plots (Scottish Rural Action, 2020).

This fondness for the rural idyll and the presence of second homes part of the cultural heritage in Scotland is to an extent reflected in the case of Ireland. The urban to rural migration phenomenon has been underway for generations and the pandemic-induced transition from on-site to remote working in cities has further accelerated this inverse process (Nordic Talks, 2021). Several Irish towns and villages have transformed into low-density, temporary, green havens for the urban generated rural dwellers (Noonan, 2021). The commute is no longer of the essence given remote working. Among migrant workers, families, and retirees, there has been an increased interest in buying detached private properties or “one-off housing” in the outskirts of Ireland, especially the rural west coast (Hutton, 2020). The Irish government intends to take advantage of this shift in the psyche—by moving away from mass tourism, which has indeed aided in economic diversification in the past but has worked as an extension to the urban market (Nordic Talks, 2021). Instead, Irish policymakers intend to promote a sustainable, rural revival by considering the rural perspective. Factors defining peripherality such as closely-knit communities, and a pluralistic work-life balance have allowed Irish rural communities to effectively respond to COVID (Fisher, 2021a). These are strengths that can be further developed with investment in physical infrastructure like high-speed broadband and sourcing suitable buildings to make rural towns viable for remote work (Fisher, 2021a). The case study of Ireland will be explored further in this paper.

3 “One-off” housing and Ireland’s suburban sprawl

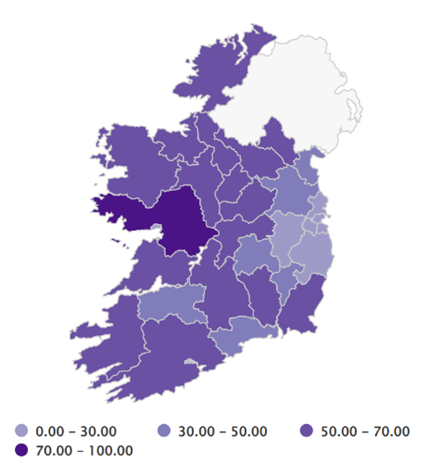

| Figure 1: Percentage of homes constructed since 2011 that are one-off houses, 2016 (Central Statistics Office, 2021) |

Similar to the other partners of the Northern Periphery and Arctic Program, Ireland’s permissive housing policies continue to facilitate widely dispersed, suburbanized settlement patterns—“one-off” housing estates being one of its defining features (Meehan, 2021). “One-off housing” refers to self-built, detached properties in the countryside, see Figure 1 (Meehan, 2021). The one-off housing debate in Ireland sparked in April 2001 when the Department of the Environment revealed that 30-40% of the annual home completions are single houses (characterized by their 58-meter-frontages) in the countryside—these were properties that were becoming increasingly opted for by urban migrators (Nix, 2003). Currently, 26% of the two million occupied housing in the country can be categorized as “one-off” housing estates (Central Statistics Office, 2021). For perspective, 60-70% of all new housing in counties Galway and Wexford is categorized as one-off housing (Nix, 2012). An “urban generated rural dweller” is said to live in a single house in the countryside, but commutes to a city or town for work (Nix, 2003). According to the Central Statistics Office, the demographic commuting to work for greater than 30 minutes have higher incomes, which suggests that much of the “counter-Urbanism” is largely based around the middle-class flight (Central Statistics Office, 2021). Urban-based rural dwellers opt for one-off housing since they promote privacy, allow families to reside near relatives, bear minimal site costs, and can be self-built to fit taste. Moreover, these estates allow farmers to effectively live on their land, with time-saving and security benefits (Meehan, 2021). However, the current Irish one-off housing phenomenon is generally disconnected from agricultural practices—the Teagasc Farm Survey indicates that there are 140,000 farms in Ireland compared to the 442,669 one-off dwellings (Dillon et al., 2021).

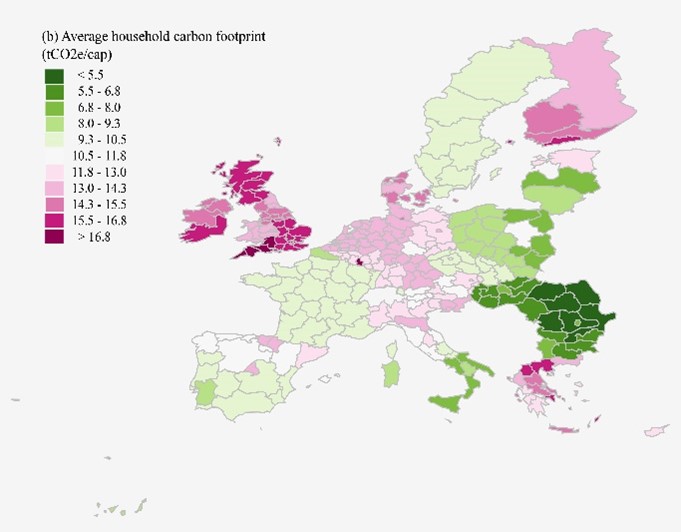

The construction of one-off housing estates in the countryside is the most graphic manifestation of suburban sprawl (EPA, 2008). Over the past two decades, this dispersed settlement pattern has consequently led to the footprint of Dublin to double or even triple that of European cities with similar-sized populations (see Figure 2) (EPA, 2008).

| Figure 2: Average household carbon footprint (Hennigan, 2020) |

The widespread construction of single dwellings in the periphery of urban centers is an unsustainable manner of living in contrast to closely-knit housing developments (with c.a. 5-meter-house-frontages) that feature collective service functions: mail delivery, waste collection, septic tanks, phone and electricity connections, footpath provision or public lighting (see Figure 3) (Nix, 2003). Despite the trend for commuter living, the infrastructure and transport links from the sprawling suburbs to the city have been inadequate (Mullen, 2014). These suburbs experience a constant process of infrastructure catch-up on the building of new roads, services, and amenities that attempt to connect homes with places of work—contributing to Ireland’s high levels of car dependence (NPA, 2019). These poorly serviced commuter towns are in need of structural reforms and rural revitalization if they were to sustain the migrating population post-COVID.

| Figure 3: Distance of one-off housing from town by year built, 2016 (,20) |

According to the Irish Rural Dwellers Association, rural institutions like schools, post offices, and the lack of critical infrastructure are under constant threat of suburbanization (IFA, 2015). The dispersed “one-off” housing properties further amplify these issues. For instance, parts of Ireland are categorized as “too rural” for the provision of ambulance services and hospitals—thus requiring people to travel long distances for receiving health care (IFA, 2015). Additionally, given the greater range of commercial services and infrastructural networks in cities, more people are likely to bypass local towns and villages, and settle in the suburbs. “One-off housing” properties thus rob rural towns and villages of their collective service functions, vibrancy, and local economies—further dragging the rural hinterlands into the commuter catchments of larger cities (McDonald, Nix, 2005). This form of dispersed living erodes local services and amenities that are vital towards maintaining socially cohesive, vibrant rural communities.

4 Paradigm shift from Urban to Rural during COVID

The Coronavirus pandemic has induced a transition from on-site to remote working in cities—softening demand for commercial office spaces and in turn accelerating the urban-to-rural migration process (Noonan, 2021). Several Irish towns and villages have thus transformed into low-density, temporary, green havens for the urban generated rural dwellers. Online property search data is indicative of an attitude shift amongst home buyers, with an increased interest in affordable individual housing units in the outskirts of counties Galway, West Cork, Mayo, Westport, Roscommon, Kerry, and Donegal (Hutton, 2020). The preference is decreasing for traditional commuter belt counties like Wicklow, Kildare, and Meath, as home buyers opt for developments in the rural, west coast (Hutton, 2020). The regions with the highest share of one-off housing are in the West coast (42%), Mid-West (31%), and South-West (29%). Northwest Ireland generally has the highest proportion of one-off housing (see Figure 1); the region is one of the most economically disadvantaged of the country with few urban settlements (Central Statistics Office, 2021).

The following subsection aims to discuss the socio-cultural and economic factors in Ireland that contribute to the shift in preference from urban to rural housing during COVID.

4.1 Sociocultural and economic factors

With the opportunity of remote working during COVID, potential home buyers are opting for houses in the outskirts with picturesque greenery and pastoral landscapes (Hutton, 2020). The pastoral backdrop of the countryside holds particular resonance in Ireland (Corcoran, 2018). According to Rowe, “pastoralism continues to serve as a critical lens through which to mark human progress and as an optimistic source for dealing with threats encroaching from either a natural or suburban wilderness” (Rowe, 1992, p. 226). Historically, Irish nationalism has maintained an uneasy relationship with urban life, and the status of Dublin as the center of Ireland has long since been ambiguous (Horgan, 2004). Since Ireland’s Independence in 1922, the view that Irishness and urbanity were in a contradictory relationship became prevalent (Horgan, 2004). Whilst the idea of the rural peasantry became the essence of Irishness, it also articulated a view that was anti-urban. The trope of anti-urbanism is still deeply embedded in Irish culture and politics. In contemporary Ireland, Dublin’s rapid expansion and increased cosmopolitan essence have received cynicism from those who feel that these changes have led to material impulses perceived contrary to the identity of the Irish (Horgan, 2004).

The large-scale conversion of former agricultural lands into “one-off housing” properties in the suburbs is in part reflective of the people’s fondness for the rural idyll and their aversion to high rise (Mullen, 2014). According to the 2020 census, only a staggering 8.2% of the Irish population lives in apartments (Eurostat, 2020). The rest of the population does not prefer apartments regardless of their convenience; a strong attachment to the land is in the psyche of many Irish people (Mullen, 2014). The shift in lifestyle choices prompted by COVID and the urge to move back to the rural regions is partially reflective of Ireland’s historical “counter-urban” sentiment.

Although the agricultural sector has been categorized as essential activity during COVID and maintained during lockdowns, labor-intensive sectors (agriculture, food-processing, mining, and forestry) that are critical for the rural economies are experiencing shortages in workers and a disrupted food supply chain; this is primarily associated to border closures, disruptions in logistical services, and additional impacts of Brexit (OECD, 2020). Future threats of climate change, Brexit, and automation will be felt more harshly in the outskirts of Dublin and cities located further away—leading to even more unbalanced regional disparities and an escalated housing crisis in the capital (Social Justice Ireland, 2021). If a sustainable shift does not take place in the rural regions and companies revert to “business as usual”, the population shift and any rural policy action will be inefficient in maximizing equal economic recovery for all parts of the country (OECD, 2020).

5 Scope for revitalization in rural Ireland

The Irish Government aims to capitalize on and utilize the inclination of potential home buyers to live in rural areas, as an opportunity to tackle the dispersed suburban settlement issue post-COVID (Dept., 2021). “Our Rural Future: 2021-2025” is a government initiative with the aims of reversing acute rural decline and addressing rural housing in a broader regional development and settlement context. It seeks to tackle Ireland’s dispersed suburban development and protect these areas from unsustainable over-development (Dept., 2021). The current urban generated hemorrhaging of scattered “one-off” housing isolates dwellers from supermarkets, GPs, and pharmacies, and is associated with increased roads and commuting costs (Taylor, 2008). It is key to develop spatial strategies focusing on how dwelling typologies and building density can be optimized in response to the urban-to-rural migration, which is predicted to escalate the suburbanization process. Two such spatial strategies, as opted for in the post-COVID regional plan in Ireland will be discussed in the following subsections.

5.1 Remote working hubs and revitalized town centers

In order to stimulate innovation within local economies, the government intends to invest in enterprise space with remote working facilities and co-working hubs in rural towns (Dept., 2021). A network of 400 remote working hubs—a pilot scheme converting local pubs into multi-purpose communal spaces—and revitalized town centers (parks, green spaces, and recreational amenities) aim to spur rural rejuvenation, whilst relocation grants and tax incentives will be introduced for businesses to support home working (Noonan, 2021). COVID containment measures instigate remote working practices, remote learning, and e-services—which are of the essence in rural regions regardless of COVID—where the commute tends to be longer; indeed, the increased connectivity of services through broadband and investment in public infrastructure aim to further spur employment opportunities and encourage rural-urban linkage (Department of Rural and Community Development, 2021).

With its rural investment, the government seeks to acknowledge the commercial and communal activities in rural areas but also recognize the challenges faced by the dwellers (Dept., 2021). These challenges include the effect of vacant and derelict properties on the vitality of towns and the impact of online shopping on town-center retail. The pandemic has highlighted the importance and convenience of shopping locally, and the government intends to invest further in rural revitalization to support the viability of local businesses and further promote residential occupancy in town centers (Dept., 2021).

5.2 Optimizing dwelling typology & building density

“Our Rural Future” aims to place town centers in the heart of decision making. Locating communal services such as schools or medical services in town centers rather than in the outskirts aids in town revitalization by increasing footfall and by creating a sense of space (Dept., 2021). Another approach involves utilizing existing buildings and unused land for new development to promote residential occupancy (Dept., 2021).

The new regional plan is inspired by the New Urbanism movement—an urban design movement popularized in the US during the 80s, which seeks to foster ecologically-sensitive, walkable neighborhoods (Nix, 2003). This transit-oriented development (TOD) suggests an end to cars and the commute for remote workers. Shops and houses are arranged to ease commute by foot or bike (NPA, 2019). Well-laid out parks, green spaces, and town squares are key to creating a vibrant center. New Urbanism also involves sensitive and effective land use with the aim of reducing under-utilization and dilapidation. The National Planning Policy thus aims to deliver a minimum of 40% of Ireland’s new housing within the existing build-up of cities, towns, and villages on infill/landfill sites (NPA, 2019).

New Urbanism also dictates high-quality design development and architectural diversity within communal living (Nix, 2003). Since the ability to self-build a family dwelling suited to one’s needs at an affordable cost in the countryside is a key driver to Ireland’s settlement pattern—it can be used to foster creativity and innovation. For example, by providing an option for people to upsize and build a house of their own layout on a larger site yet within walking distance to amenities such as schools, churches, and sports facilities (Dept., 2021).

6 Evaluating “Our Rural Future”

The rural communities of Ireland in 2025 will be determined by the extent to which they can successfully adapt to support the future of work, whilst transitioning into a more sustainable society.

With the execution of “Our Rural Future”, the government seeks to exploit the shift in workplace habits promoted by COVID (Hutton, 2020). Flexible workspaces a short commute away from home, alongside grants and tax incentives are measures promoting workers to remain in or move to rural Ireland in the thousands (Dept., 2021). Trade unions such as the Irish Congress of Trade are in complete favor of this shift, claiming that remote working has the potential to be a win-win opportunity for both workers and rural areas (Wall, 2021). Remote digital connectivity and increased capacity of remote learning will enable the youth in rural areas to access higher education within local communities—helping reverse generations of depopulation, brain drain, and ingrained migration (Wall, 2021). Reducing the digital divide through broadband rollout will help address shortcomings in physical infrastructure such as transport links (Noonan, 2021).

Although remote working will drive people back to rural areas, an overreliance on home working must be avoided since not everyone has a suitable area at home to work from. Thus, as lockdowns ease, the availability of office spaces and working hubs in towns and villages becomes critical to the success of the strategy (Noonan, 2021). In order to achieve social cohesion, the 400 working hubs need to focus not only on start-ups and creatives but also on integrating local communities by facilitating classrooms or gatherings of people.

Key to the rejuvenation plan is an integrated, place-based outlook in order to maximize investment and meet long term needs of rural areas (Dept., 2021). This is achieved through a “town-first” approach, with the intention of attracting retail and commercial premises to the center of towns rather than the outskirts (Dept., 2021). Inspired by the New Urbanism movement, all new houses will be built in clusters close to the main street and dispersed one-off housing will be avoided. According to reports from the Central Statistics Office, currently, the average distance to most everyday services for rural dwellings is 3 times that of urban dwellings (Central Statistics Office, 2021). Provision of adequate services and infrastructure close to home is thus critical to the success of the plan. The COVID-induced psyche of shopping locally is also reflected in the plan; the plan will support local businesses and retail stores in order to promote residential occupancy in town centers (Dept., 2021). The plan also focuses on converting pre-existing vacant and derelict properties into remote workspaces, green spaces, and recreational amenities to make vibrant hubs for community engagement (NPA, 2019). Improved land use in turn aids in promoting green tourism, and employment opportunities in the rural communities within the fields of renewable energy, bioeconomy, and sustainable economy (NPA, 2019). These factors will assist rural Ireland to move past the aftereffects of Brexit and post-COVID recovery (Social Justice Ireland, 2021).

6.1 Skepticism

Ireland’s last decentralization push, now labelled as the “decentralization debacle”, occurred in 2003 when government department buildings and civil servants were moved from the capital Dublin to different towns across the country (Noonan, 2021). It involved the dispersal of 10,992 public servants based in Dublin to 58 different locations in 25 counties (McCreevy, 2017). The headquarters of 8 government departments were moved to counties as far apart as Cavan and Killarney (McCreevy, 2017). This initiative however granted fewer employment opportunities and policy changes than expected (Noonan, 2021). The program did not comply with what is traditionally understood as “decentralization”, which involves a proper transfer of power from the center to the elected authorities at the local branches who receive some degree of autonomy in relation to policymaking—an idea that is more complex than simply moving around buildings of the central government (McCreevy, 2017). The 2003 decentralization initiative was essentially about spreading development, but the development remained in Dublin. No new policy formations thus came into effect in these rural outskirts, and the “Dublin-mindset”, the idea of central decision-making limited to the capital, thus remained (McCreevy, 2017).

With its “decentralization”-inclined approach, “Our Rural Future” seeks to achieve balanced development across the country; however, this approach has been historically proven elusive and regarded as a hindrance to long-term national growth (Dept., 2021). The proposed plan aims to balance growth throughout Ireland and reduce rural decline by ensuring that provincial cities like Waterford, Cork, and Donegal can act as a counterbalance to Dublin (Hutton, 2020). From an inclusive point of view, this proposal appears great. But regional disparities, that exist due to underlying economic competencies and varying industrial dynamics, make it difficult to achieve balanced growth across regions (Crowley, 2019). This is the reason why agglomerations like Dublin exist—as services linked to technology, culture, education, and leisure are easily accessible by people, a cluster of firms, and organizations in geographical proximity (Crowley, 2019). Moreover, larger cities have always had larger labor pools, improved infrastructure, and access to resources. DublinTown argues that “Our Rural Future” with its work-from-home incentives is “anti-Dublin” bias, and they fear for a loss in foreign direct investment from organizations seeking the quality of life provided by urban settings (Noonan, 2021). They believe that shifting major businesses to areas in the far outskirts of Dublin will be fruitless, since these regions are lacking in the technology frontier, skilled labor and as a result, in their ability to attract customers (Crowley, 2019). They also suggest that under-resourcing the capital city will place the Irish economy on the wrong trajectory. It will also contribute to a misallocation of the taxpayer’s money (Noonan, 2021).

DublinTown claims the government’s redevelopment approach to be overly optimistic and believes that the short-term approach only draws on the current psyche of the people dissatisfied with urban living during lockdown (Kelly, 2021). Given the attractiveness of urban centers for modern life, encouraging workers to stay away from the capital is guaranteed to fail (Noonan, 2021). Before the pandemic, cities had proven how urban centers can encompass educational, leisure, entertainment, and cultural opportunities (Kelly, 2021). Dublin has disproportionately borne the brunt of the virus containment measures, but lessons from the past prove that cities are the best place to rebound and regenerate economic activity (Kelly, 2021). Dublin will thus continue to play a predominant role in Ireland’s future, where the population growth will predictably outweigh that of surrounding regions by 2040 (Crowley, 2019). Despite the argument of over congestion, Dublin’s growth-share in jobs has been rising over the last two decades (Kelly, 2021). It is therefore short-sighted by the government to forgo these opportunities in its regional development plan.

6.2 The case for “real decentralization”

Ireland is fertile ground for a decentralization initiative given the “counter-urban” sentiment of the people when it comes to housing development (Horgan, 2004). But in order to reap the benefits of such a plan, the government needs to aim for “real decentralization”, which proper transfer of power from central Dublin to the local authorities who gain control over decision-making regarding revenues, spending on services, infrastructural policies, housing, education and health (McCreevy, 2017). Consequently, with an increased need for providing services and collecting revenues at a local level comes the need for a share of civil servants from Dublin who will be relocated to rural towns (Noonan, 2021). The Minister of Rural Development Heather Humphreys claims “Our Rural Future” to be a “modern-day, worker-led decentralization” movement, with the 300,000 civil servants/remote workers playing a key role (Wall, 2021). In contrast to the “decentralization debacle” of 2003, the government outlines in its regional plan that the paradigm shift will be carried out by the people (Wall, 2021). This manner of gradually increasing local government capacity in order to facilitate policy changes is already in play in the Nordic countries and Switzerland (Crowley, 2019).

The outskirts of Dublin and regions further out will be most affected by the threats of climate change, Brexit, and automation—leading to even more unbalanced regional disparities and an escalated housing crisis in the capital (Social Justice Ireland, 2021). This is why the government considers “Our Rural Future” as the much-needed intervention to disrupt the pro-Dublin development bias (Dept., 2021). Despite its optimistic growth plans outside of Dublin, there are indeed limitations to the plan associated with the per capita spending at the county level—Dublin will be receiving the highest financial support in the context of Ireland’s 2018-27 budget (Crowley, 2019). This will undoubtedly restrict the ability of “Our Rural Future” to meet regional convergence and its population target growths set for areas outside of the capital. Vast areas of the country such as the Northwest will be receiving little financial aid, which will worsen urban sprawl and dispersed development (Crowley, 2019). One of the biggest limitations of the regional development plan may be that it is being executed with a largely unchanged institutional top-down approach, with the exception of some proposals for change at the regional level. A top-down national approach should ensure place-based, spatially blind policies and institutions in pivotal developmental areas (Crowley, 2018). The top-down approach dictates that the priorities of the government must shift to connective infrastructures like roads, railways, and broadband to reduce the economic distance for firms (Crowley, 2018). To futureproof the vibrancy of villages, “Our Rural Future” indeed mentions successful bottom-up tactics. A bottom-up approach deals with local and regional governance; it focuses on the different needs and structures of the individual counties to maximize their growth potential (Crowley, 2018). It demands local and regional policies that cater to their needs, which in turn affect the residential and local investment needs of the areas. To deal with the issue of under-resourced regions, one idea is the provision of funding through substantial land value tax to reduce inefficiency and fund local services (Crowley, 2018). DublinTown claims that a decentralized plan will lead to a misallocation of the taxpayer’s money, but the unsustainable, widely dispersed settlement patterns in the suburbs already consume more tax income than they generate and the properties are cross-subsidized. Additionally, the affordability of servicing and maintaining basic services such as roads, post offices, and broadband in dispersed settlements has a direct cost on one-off dwellers themselves. This results in the frequent withdrawal of services, leading to disparities in the provision of amenities and services in the rural regions. This further reinforces the importance of a combined bottom-up, top-down approach. The relocation of workers to the regional hubs is designed to generate further business and encourage autonomy in decision-making so that they can guide their own growth in the future (Noonan, 2021). Waterford, Donegal, and Cork have great potential for socioeconomic rejuvenation (Hutton, 2020). The implementation of both top-down and bottom-up rejuvenation strategies by the government in rural Ireland will help determine the success of the current plan in comparison to the 2003 decentralization debacle.

Ireland’s population is expected to grow by a factor of a million in the next two decades—which means 550,000 more houses and 660,000 new jobs (Dept., 2021). Expansion of smaller cities and villages in the North, South, and the Midlands thus becomes critical in order to ease congestion in Dublin. With its plan, the government intends to ensure that rural Ireland does not suffer drains in experience as people continue to relocate to Dublin for employment (Dept., 2021). The main way of achieving this is by encouraging people to live in town centers—as opposed to relocating to the capital—and by redistributing employment per region by decentralizing various industries (Dept., 2021). This will help in achieving viability and economies of scale in smaller cities.

Pandemic or not, the dispersed living is unsustainable from the urbanism point of view and must be tackled by the government. A dispersed settlement increases car dependency and the cost of providing services such as broadband, electricity, and ambulances leading to car dependency whilst diminishing the social life and viability of rural communities (IFA, 2015). With the building of integrated neighborhoods modelled on the basis of New Urbanism, green parks, and town squares— the government simply plays the role in infrastructural catchup by facilitating hubs for remote working, clusters of housing around the existing build-up of villages, broadband rollout, schools, roads, hospitals, etc. (NPA, 2019)

The government believes in the need to futureproof the vibrancy of both cities and villages in Ireland (Dept., 2021). Decentralization will help ease the housing crisis, reduce transport congestion in the city, and will help provide much sought-after office space by repurposing pubs in rural towns (Dept., 2021). Whilst the government’s plan is to be welcomed, it is not without its challenges. It has received a fair amount of opposition from city-based businesses and organizations, claiming that it will hinder Dublin’s ability to attract Foreign Direct Investment and that workers seek the quality of life provided by cities (Noonan, 2021). Even though Ireland is still at an early phase in building a remote working culture, the government’s plan shows a step in the right direction. In order for this plan to succeed, remote working can no longer be a one-off deal between employees and employers. A systematic approach is required to embed remote working into the economy, for example, with incentives to maintain remote jobs as remote, as outlined in “Our Rural Future” (Dept., 2021). Remote working brings the opportunity for a much-awaited cultural shift. Businesses, the government, and the community need to make a collective approach in driving the occupancy of the co-working hubs. Companies need to advertise open roles as location-agnostic, such that rural communities have the visibility of opportunities. “Our Rural Future” is fundamentally about equal access to opportunity. The government must manage a drift to towns and villages rather than one-off housing since that increases the cost of provision of basic services like GPs and schools (NPA, 2019).

There are a few other limitations associated with “Our Rural Future”, for example, the manner in which its success can be measured. The plan simply outlines that the government intends to maximize the number of families living outside of big cities, but that is not a concrete manner that helps decipher the extent of rural rejuvenation or progress made in sustainability. A few potential ways of measuring success are, for example, the number of jobs generated, the number of new start-ups and entrepreneurship, the number of enrolments in school, or the reduction in one-off housing per county.

The planning framework indeed encourages the cluster living permitted around a given radius surrounding towns and villages. No more one-off housing will be permitted in extremely rural areas with the exception of farmers who cultivate surrounding land. This raises a number of questions. What happens when someone inherits that piece of land—will they be expected to continue farming? What is to be done with the existing one-off housing? How can a distinction be made between the one-off urban sprawl, accounting for c.a. 70% of incidents, and the more sentimental Irish rural housing idyll that is so important to its culture?

7 Conclusions

The 9 partners of the transnational cooperation Northern Periphery and Arctic Program—Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Ireland, Northern Ireland, the UK, Faroe Islands, and Greenland—share a number of aspects in common: a sparse population growth, youth out-migration, brain drain, and an increasingly ageing population are their defining demographic characteristics. The defining features of the Northern Periphery regions such as close-knit communities, pluralistic work-life balance, and localized services have helped remote regions respond more effectively to the pandemic (Nordic Talks, 2021). COVID-19 has impacted not only the daily life in rural communities of these NPA regions but also their local tourism. The pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have demonstrated the economic and social consequences of an excessive dependency on international tourism during crises (Fisher, 2021b). Advocates of sustainable tourism believe that a form of “regenerative tourism” is needed to promote trends of tourism equity and a revival of the rural areas in the post-pandemic age. This form of rural revival may be supported by the pandemic-induced shift in workplace mobility. As lockdowns and social distancing restrictions force the greater part of the global population to stay home for extended periods, access to green spaces and large private spaces have become a luxury (Åberg et al., 2021). Competing trends of a second-home boom, advancement in ICT and teleworking, and the longing for the rural idyll have the potential of spurring rural rejuvenation by attracting city dwellers to relocate, at least seasonally, in sparsely populated rural areas.

Understanding the broader context and characteristics of the NPA regions in Europe allows further investigation of the case study Ireland. Similar to the other regions part of the Northern Periphery and Arctic Program, rural Ireland has also been confronted by several pressures with the advent of the Coronavirus pandemic. “One-off housing”, the rural residential typology common in Ireland, refers to self-built, detached properties in the countryside and is the most graphic manifestation of Ireland’s suburban sprawl (EPA, 2008). Census data shows that the main drivers of “one-off” housing is a suburbanized lifestyle, permissive policies, affordability, and proximity to large towns which can offer employment and services within easy reach by car—whilst having a backdrop of the pastoral landscape (Central Statistics Office, 2021).

COVID has induced a shift in attitude amongst home buyers; the opportunity of remote working has increased interest in affordable individual housing units in the outskirts of cities (Hutton, 2020). The Irish government took this as an opportunity to execute its regional development plan “Our Rural Future: 2021-2025” with the objective of tackling dispersed development in Ireland and protecting areas from inappropriate over-development (Dept., 2021). Alongside socioeconomic rejuvenation in the Brexit climate, the country’s cultural identity will be enriched by the urban-to-rural migration since Ireland’s heritage lies in the heart of its rural landscape, flora, and fauna (Corcoran, 2018). With the building of integrated neighborhoods modeled on the basis of New Urbanism, green parks, and town squares— the government aims to play the role in infrastructural catchup in a “modern-day, worker-led decentralization” movement (Wall, 2021). By encouraging migration from urban to rural whilst tackling the overall historical pattern of dispersed development, the regional development plan will protect areas that are under strong urban influence from unsustainable over-development (Dept., 2021).

It is critical to note within the scope of this paper that Ireland, in comparison to many other European countries, has a more fertile ground for the implementation of a such policy given its fondness for the rural idyll. Its “counter-urban” sentiment is rooted in its culture, reflected in the dispersed development and lack of high rise in the capital city (Mullen, 2014). These factors will largely contribute to the success and acceptance of the government’s redevelopment plan.

However, there are a number of limitations to “Our Rural Future”. The plan seeks to achieve balanced development across the country; however, this approach has been historically proven elusive by the 2003 “decentralization debacle” (Noonan, 2021). The current plan does not have an exit strategy for Dublin in the long term. City-based businesses and organizations thus fear a loss in Foreign Direct Investment from organizations seeking the quality of life provided by urban settings (Noonan, 2021). DublinTown claims the government’s redevelopment approach to be based on a potentially short-term trend and believes that it only draws on the current psyche of the people dissatisfied with urban living during lockdown (Kelly, 2021). Furthermore, regional disparities will make it more difficult to achieve balanced growth across regions (Crowley, 2019). This is one of the main contributors to why agglomerations like Dublin exist—as technological, cultural, educational, leisure and entertainment services are most easily accessible by the people and clusters of firms in geographical proximity (Crowley, 2019). Dublin’s growth-share in jobs has been rising over the last two decades (Kelly, 2021). Indeed, it would be short-sighted by the government to forgo these opportunities in its regional development plan. The success of the plan is to a large extent dependent upon the attitudes of how employers adapt to the new norm. The plan does not propose a concrete solution to the existing one-off housing or ways to assess the success of the “rejuvenation” objective.

Given the government’s relocation grants and tax incentives, the shift from urban to rural will be gradual; it is unrealistic to expect a mass exodus of people to move to the rural because of the attractive opportunities provided by an agglomerate like Dublin. The plan must be executed keeping in mind both top-down and bottom-down approaches, or else it may risk the same failures as the 2003 decentralization debacle.

Overall, “Our Rural Future” is a bold attempt at turning the pandemic into an opportunity to address long-standing issues of sprawling development and derelict rural life, although the decentralization-inclined approach runs the risk of creating conflict with Dublin and would benefit from a more thorough analysis of costs and benefits.

References

Benjamin, S., Dillette, A., & Alderman, D. H. (2020). “we can’t return to normal”: Committing to tourism equity in the post-pandemic age. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759130

Central Statistics Office. (2021, February 15). Occupied Dwellings – CSO – Central Statistics Office. Census of Population 2016 – Profile 1 Housing in Ireland. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp1hii/cp1hii/od/.

Corcoran, M. P. (2018). The Irish Suburban Imaginary. Imagining Irish Suburbia in Literature and Culture, 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96427-0_3

Crowley, D. F. (2018, February 16). Why Project Ireland 2040 is doomed to fail. RTE.ie. https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2017/1206/925347-irelands-national-development-plan-is-doomed-for-failure/.

Crowley, D. F. (2019, October 7). Why Ireland needs real decentralisation. RTE.ie. https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2019/1007/1081547-why-ireland-needs-real-decentralisation/.

Cundy, A. (2020, December 11). The islands and idylls of rural Scotland lure the lockdown-weary. Financial Times. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.ft.com/content/6bd8aea8-fa26-4336-960e-dcc25a14bd96.

CarbonBrief. (2017, May 31). Mapped: How ’embodied’ footprints compare across Europe. Mapped: How ‘embodied’ footprints compare across Europe. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-how-embodied-carbon-footprints-compare-across-europe.

Department of Rural and Community Development, Government of Ireland, Our Rural Future: Rural Policy Development 2021-2025 (2021).

Dillon, E., Donnellan, T., Moran, D., & Lennon, J. (2021). (rep.). Teagasc National Farm Survey 2020 Preliminary Results.

EPA. (2008). (publication). Ireland’s Environment 2008 (p. 255). EPA Publications.

ESPON. (2019). (rep.). Balanced Regional Development in areas with Geographic Specificities (Vol. 1).

European Commission. (2020). EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380

Eurostat. (2020). (rep.). Housing in Europe Statistics Visualized (p. 5). Luxembourg City: Eurostat Publishing.

Fisher, T. (2021, April). (rep.). NPA COVID-19 RESPONSE PROJECT ON ECONOMIC IMPACTS, Part 1: Key Findings, Recommendations and Summaries. CoDeL.

Fisher, T. (2021a, April). (rep.). NPA COVID-19 Response Project on Economic Impacts, Main Report – Part 4: Time for a radical change? Shifting to genuine sustainable urbanism. CoDeL.

Fisher, T. (2021b, April). (rep.). NPA COVID-19 Response Project on Economic Impacts, Main Report – Part 5: Resilience factors in peripheral areas of the NPA. CoDeL.

Hennigan, M. (2020, January 1). House size of Ireland’s urban-generated rural dwellers jumps 29%. Finfacts Ireland. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.finfacts-blog.com/2021/03/house-size-of-irelands-urban-generated.html.

Horgan, M. (2004). Anti-Urbanism as a Way of Life: Disdain for Dublin in the Nationalist Imaginary. The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 30(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.2307/25515532

Hutton, B. (2020, July 18). Interest in rural property soars as Covid-19 effect kicks in. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/interest-in-rural-property-soars-as-covid-19-effect-kicks-in-1.4307247.

IFA. (2015). The Rural Challenge: empowering rural communities to achieve growth and sustainability. Kerry.

Kelly, O. (2021, March 29). Rural revival plan shows ‘anti-Dublin bias’, says business group. The Irish Times.

McCreevy, C. (2017, January 8). Moving in the wrong direction: the decentralisation debacle. Independent.

McDonald, F.; Nix, J. (2005). Chaos at the crossroads. Gandon Books.

Mullen, R. (2014, February 28). The Irish Aversion to High-Rises and How Dublin is Dealing with Urban Sprawl. The Global Grid. https://theglobalgrid.org/the-irish-aversion-to-high-rises-and-how-dublin-is-dealing-with-urban-sprawl/.

Noonan, L. (2021, March 30). Ireland plans home working push to shift city workers to rural areas. Financial Times.

Nix, J. (2003, September 17). Downside of one-off rural housing. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/downside-of-one-off-rural-housing

Nix, J. (2012, November 6). Urban sprawl, one-off housing and planning policy: more to do but how? https://irishplanningfutures.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/2002-islr-one-off-housing-more-to-do-but-how.pdf.

Nordregio. (2020, June 24). Will rural living become more desirable post-corona? Nordregio. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://nordregio.org/nordregio-magazine/issues/post-pandemic-regional-development/will-rural-living-become-more-desirable-post-corona/.

Nordregio. (2021, October 6). Rediscovering the assets of rural areas. https://nordregio.org/rediscovering-the-assets-of-rural-areas/

NPA. (2021, November 11). Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme . Retrieved November 24, 2021, from https://www.interreg-npa.eu/

Nordic Talks. (2021). Redefining Peripherality. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vmz5m-jUnyw.

NPA. (2019). Ireland 2040 Our Plan (pp. 85–89). Dublin: NPA Publishing.

OECD. (2020, June 16). Policy implications of Coronavirus crisis for rural development. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/policy-implications-of-coronavirus-crisis-for-rural-development-6b9d189a/.

Social Justice Ireland. (2021, March 29). ‘Our Rural Future’ – Rural Development Policy 2021-2025. Social Justice Ireland. https://www.socialjustice.ie/content/policy-issues/our-rural-future-rural-development-policy-2021-2025.

Taylor, M. (2008). Living working countryside: the Taylor review of rural economy and affordable housing (Vol. 1). Department for Communities and Local Government.

Petrov, A. N., Hinzman, L. D., Kullerud, L., Degai, T. S., Holmberg, L., Pope, A., & Yefimenko, A. (2020). Building resilient arctic science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Communications, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19923-2

Rowe, P. G. (1991). In Making a middle landscape (p. 226). essay, MIT Press.

Scottish Rural Action (2020). (rep.). Rural Communities Survey on COVID-19 – Response and Recovery (Vol. 1).

Slätmo, E., Ormstrup Vestergård, L., Lidmo, J., & Turunen, E. (2019). Urban–rural flows from seasonal tourism and Second Homes: Planning Challenges and strategies in the Nordics. https://doi.org/10.6027/r2019:13.1403-2503

Meehan, Stella. (2021, April 27). One-off rural housing ‘vital’ for rural Ireland’s survival – canney. Agriland.ie. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.agriland.ie/farming-news/one-off-rural-housing-vital-for-rural-irelands-survival-canney/.

Svanberg, K. (2021). (rep.). an Rights in Times of COVID-19: Camping on Seesaws when balancing a State’s Human Rights Obligations against the Economy and Welfare of its People (Vol. 1). CoDeL.

Vass, T. (2021, April 2). Multi-local living broadens our understanding of urbanisation. Kvartti. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.kvartti.fi/en/articles/multi-local-living-broadens-our-understanding-urbanisation.

Wall, M. (2021, March 29). Remote working likely a ‘win-win’ for workers and rural areas – unions. The Irish Times.

World Tourism Organization. (2021, November 26). 2020: Worst Year in Tourism History with 1 Billion Fewer International Arrivals.

Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals.

Åberg, H.E.; Tondelli, S. Escape to the Country. (2021). A Reaction-Driven Rural Renaissance on

a Swedish Island Post COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212895